In the first and second year of KA it was not uncommon that I would hear things from students like, “This Shakespeare is amazing!” or “I never read an entire book before,” or “Doing a play is more exciting than I imagined,” and of course the ubiquitous, “I never liked history before,” all absorbed and transfixed in the wonder of what they were doing and experiencing.

So here we are, at the very end of the fourth year of the school, two hours away from my getting on a plane that will take me to Paris and then to Cincinnati for summer vacation. What is it like now at the end of the fourth year?? For experienced educators, there can be great danger in losing the wonder. The improvements in the school or students that once thrilled us may become more familiar and academic. We may fall into the lethargy of using our minds but not always our hearts.

I have not found it hard to keep growing in wonder, however. I am still moved by what we have done in these four years, and the possibilities of where our students might go. It is still enormous work here, but very satisfying work. I am reminded of the great Stephen Sondheim song, “Finishing the Hat,” in Sunday in the Park With George when George sings, “Look, I made a hat…where there never was a hat.” Look—we made a school, where there never was a school!

It is not hard to keep growing in wonder when I look at two of my colleagues, both of whom have turned 70 in the last 3 weeks. Joan and Nancy have been teaching since the year I was born, and they are vibrant, warm, enthusiastic, optimistic, necessary, and full of wonder themselves. It is not hard when you work for such a good man as our headmaster, John. He is visionary, intelligent, humorous, considerate, hard-working, and believes in the “hat,” the mission of the school. Julianne has had an outstanding year, tightening up the structure of the school and ensuring that we run a tight ship. The tight ship means we can focus on all the good things of a school. It is not just structure, but a matrix upon which we can rely so we get to do the good stuff, to keep exploring new layers of wonder.

I am still in wonder at what is going on in the Arab world. As I look back on the last six months in this region of the world, at what many call, “The Arab Spring,” I am in wonder. How interesting, indeed, what poetic justice, you might say, that Osama bin Laden died at the exact moment he was made irrelevant by the Arab Spring. None of the wave of democratic uprisings transforming the Islamic world were inspired by bin Laden’s despotic, twisted version of Islam. Instead, they were fueled by waves of well-educated young people, including women, who want the chance to vote in free and open elections. No one in Liberation Square in Cairo chanted his name. I am still in wonder at the possibilities at what may take place.

Of course none of us knows what the four years at KA will actually do/for/to our students. But at the end of this year it is marvelous to look back at a calm year, an invigorating year, a year of great scholarship, of great thinking, of empathy, of respect and responsibility, of bittersweet loss as we graduated our first four-year class.

So I want you to know, I am still in wonder at this project. Now, I didn’t write as much on the blog this school year. In 2007-08 I wrote 90 blog entries, and then the next year I wrote 72 blog entries. In 2009-10 I wrote 63 blog entries, and this school year I only wrote 48 blog entries. Of course the excitement of seeing a camel is no longer new, but the wonder at what our work can accomplish still sets my heart racing and my brain zigzagging.

But it is time for summer. I will now take my annual sabbatical from the blog, with an update in July, but a break from the writing and pondering and planning of the blog. Someday I would love to convey some of the stories that don’t make it into the blog. It would be interesting to describe for you the horror and the humor of this insane teacher’s breakdown. It would be interesting to relay what the loss of a friendship means. It would be interesting to try and sum up what it is like to work with some difficult and inscrutable colleagues. But the point of this blog is not to air dirty laundry anyway or vent my spleen. I write this blog to communicate the wonder I feel as this project unfolds.

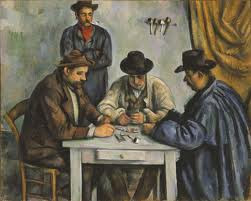

So here is to summer…here is a poem suggested to me by Steve Shapiro, a friend I made on the conference to Kathmandu last fall. The picture at the top of the page is the subject of the poem, and a kind of flower seen around in Jordan in April.

Camas Lilies

Consider the lilies of the field,

the blue banks of camas opening

into acres of sky along the road.

Would the longing to lie down

and be washed by that beauty

abate if you knew their usefulness,

how the natives ground bulbs

for flour, how the settler’s hogs

uprooted them, grunting in gleeful

oblivion as the flowers fell?

And you—what of your rushed and

useful life? Imagine setting it all down—

papers, plans, appointments, everything,

leaving only a note: “Gone to the fields

to be lovely. Be back when I’m through

with blooming.”

Even now, unneeded and uneaten,

the camas lilies gaze out above the grass

from their tender blue eyes.

Even in sleep your life will shine.

Make no mistake.

Of course, your work will always matter.

Yet Solomon in all his glory

was not arrayed like one of these.-Lynn Ungar

So in about two hours I head out for the summer. The first day of work is exactly 8 weeks from today. But for right now, I am going to do exactly what the poem suggests, I am going to set “it all down—the papers, plans, appointments, everything.” I might also do exactly as the poem suggests and when I turn the key in the apartment door lock, I may tape a note on my door: “Gone to the fields to be lovely. Be back when I’m through with blooming.”

Ahhhh…enjoy the summer. Steep yourself in wonder. Go to your own fields and be lovely!