Friday, August 19, 2011

Porters All

I love my Kindle.

When these little digital libraries first came on the market, I will admit that I was more than skeptical—in fact, I kept saying, “I wouldn’t want a Kindle ‘cause I love books too much!” I love holding books, writing in my books, displaying my books, giving books as gifts. Obviously I must like storing books since in my $100 a month storage locker in Cincinnati there are 85 boxes of books awaiting my return to the United States and properly being displayed and loved again with me in residence.

But then my former student Audra showed me her Kindle in the summer of 2009, and for every point I made, she kept saying, “You will love it—especially if you love books!!” So that Christmas my sister gave me a Kindle.

For those of you who might not yet have purchased one of these Kindles, or the other kind of e-book devices, do you know what you get to do??? Well, besides holding hundreds of e-books in the Kindle itself, one gets to download samples of books for free! For free!!!!! It’s like spending time in a book store looking through books you may just want to buy…however, I have downloaded hundreds more book samples than I could ever have devoured in afternoons in a Barnes & Noble! I mean, I gotta tell you, one way I kill time in airports (because of the usually-free WiFi) is that I look through the Kindle store and download dozens and dozens of samples of books I might enjoy.

If I open the Kindle right now, I have 438 samples of books…it’s like a kid in a candy store!!! (Again, for the un-washed, un-Kindled, a sample is about a 40-page excerpt of the beginning of a book, designed to tempt you to buy the entire e-book for around $8-10.) I have about 80 novels (yes, Anne Siviglia, I occasionally read fiction!!) and 200 samples of history books, and then the books on movie history, television history, theater history, food history, art history (yes, I am a history nut) and memoirs and humor books and books on current events. I also have a file on religious history and books on spirituality. Why not download almost any kind of book that might shed some light on…pause for a serious phrase…the human condition…

One of the more unusual samples I downloaded this summer was a book about St. Benedict, considered by many to be the founder of Western monasticism. In the year 530, Benedict composed a rulebook, “The Rule of Benedict,” by which his monks would live an ordered, holy, and monastic life.

When I downloaded the sample, I had no idea what the book would be about, but I discovered that the “rules,” the chapters were oddly interesting. Now, let’s face it, anything historical is always interesting to me. Put sports and history together—thank you to Gary Klein for helping me with this—and all of a sudden I am a sports junkie.

Anyway, back to Benedict. I think I originally downloaded the book because I have joked occasionally that working at KA in Jordan has, well, at times, felt “like a monastery on a gulag.” I mean that in an endearing way! Anyhoo, I thought the book by Benedict and all of his rules might be interesting to compare a real monastic life to my life in a dormitory in the desert 30 minutes outside of an urban area.

Huh. The entire 66th chapter of Benedict’s Rule is devoted to explicating in detail the duties of the monastery’s porter, that is, the gatekeeper or doorman. It seemed remarkable to me that one of the renowned spiritual documents of the Western world has an entire chapter devoted to how to answer the door.

Remarkable, yes, but as it has ruminated in my brain, also understandable.

Among all the brothers in the monastery, the porter alone straddles two worlds. With one foot, he is firmly located within the monastic enclosure: the world to which he has vowed his body and soul. The monastery is a regulated, all-male world—a world of black tunics, scapulas and hoods—a world of silence, simplicity, poverty, chastity and habitual prayer.

However, the porter, alone among his brother monks, also has a foot in the world without: the world as it flows by the monastery’s door, bearing with it its flotsam and jetsam of noise, bustle, color, chaos, confusion, disorder and temptation.

It is the porter’s main duty to exercise the Christian art of hospitality. At the sound of a footfall, or horse hoof, or knock—no matter what time of day or night—the Porter scurries to the door, flings it open and cries out: “Deo Gratias! Thank God you have come!”

For the Benedictine, the art of hospitality is a theological necessity. Genuine hospitality is the warm and practical evidence of God’s love.

For the Benedictine, the art of hospitality is something else as well: it exposes to all manner of persons and experiences. It is a way of living that renders us available to the world.

In the Benedictine world, the job of Porter is assigned to one person. That person alone in the monastery straddles two worlds.

Besides, the “kick” of learning some medieval job description, does this Chapter 66 mean anything more than a little trivial information???

Yesterday the administration at KA welcomed the new faculty for the 2011-12 school year—we have a week of orientation with them before the returning faculty join us on campus for a second week of orientation. Yes, for any school this is more orientation than you have in a decade! Be that as it may...yesterday in his opening address to our new faculty, our (I’ll say it again) wonderful headmaster John Austin read from the 2011 book by King Abdullah II from the part of what he gained from being at Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. Of all the many things he gleaned, he found that his tenure there helped him cultivate “wisdom and patience,” and understand and undergo an “egalitarian experience.” When Abdullah assumed the throne in 1999, he knew he wanted to create a school in Jordan that would do a similar thing. His Majesty has said often, and indeed wrote in that recent book, that he hopes the students from KA will “create a new tribe in Jordan, a talented meritocracy of lived lives of service and leadership.”

How exciting to work at a place that has that credo embedded in its founding. As John read from some passages of the King’s book, I thought of the lone Porter in the Benedictine monastery, and his importance of straddling two distinct worlds. His Majesty wants our students to straddle two worlds as well, the West and the Arab world, bringing the best of both to create a “new tribe.” If you know anything about the Arab world, tribal stuff is of primo importance. He wants a new tribe that is able to transcend the boundaries of old.

Straddling two worlds is hard—that rule of Benedict provides some insight about how porters go beyond the comfort zone, how they see two worlds and intermingle between and among. Think of how we all straddle various worlds. We all have a foot firmly planted in the “real” world: where might makes right, where wealth rules, where skin color and accent and bank account and education and nationality and ability, define us. Some people don’t like stepping inside another world, retreating from what could be a transforming experience. The borderlands are hard. Just the other day, I crossed over borders. I crossed over national borders. I also crossed over the border from summer into a consuming school world.

I thought about how excited I get every year for the beginning of classes—I am probably as giddy as the Benedictine porters as they fling open the door and announce: “Deo Gratias! Thank God you have come!”

As I listened to the hopes of King Abdullah II for this school, a school entering Year #5, it is clear to me he urges us all to straddle different worlds, cross borders and see what wisdom and patience can be gleaned from the experiences. I have no idea if His Majesty has Benedict’s rule on his Kindle, but I would imagine he would urge us to go beyond the single porter of Benedict’s day, and encourage and inspire that we are porters all.

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Anew

Summer ended yesterday when I landed at the Charles de Gaulle airport outside of Paris. I now spend a good deal of time in this airport every year. So far, in the last four years that I have come in and out of the Charles de Gaulle airport I have yet to actually go into Paris! I land at the Charles de Gaulle airport on my way to and from Cincinnati or Amman for my summer breaks. When I land there in late June, this signals the beginning of summer, and when I land in August it is the reminder that summer has ended. I have a 5-8 hour layover every time (and by the way, it is just enough distance outside of Paris not really to make the ride into town worthwhile!) and it gives me time to make the mental preparations to put work out of my mind, or to access the work files in my brain yet again.

When that plane touches down in Amman, I am back at work. I wait until the last minute to return, always hoping to keep the jet lag at bay, and I dive into the many, many meetings. Yesterday was a nearly 8-hour spate of meetings with the senior staff, and today I met for several hours helping prepare for the teacher orientations in the next week.

As we began our senior staff meeting yesterday, our leader, the wonderful head of school John Austin, reminded us that each year “we have the chance to create the school culture we seek anew.” Yes, indeed-y, that is one of my favorite things about the school world. You have this break, you shake off the travails of the year, and then you get that chance to start fresh, to begin anew.

But before we bask in the newness of the year, let me just enjoy the summer one last moment as I put it in the memory book.

What was the best part of summer? What did I do? I mentioned a number of things in my blog entry about 10 days ago—remember, the portals I would open into the past/present/future of my life. Besides my encounters with friends and family—simply wonderful and meaningful, the best thing I did this summer was go to a performance of the Broadway play, Warhorse.

Now I don’t want to dwell too long on the dearth of theater in Jordan, but I gotta tell you, when I hit New York, I gobble up theater like a fat kid gobbles up chocolate cake. I try and go every day, and I try and see as much variety. The Broadway stuff is expensive, but there are still ways to go and see many things. Four mornings this July I went down to a Broadway theater to wait in line for a few rush tickets to be sold at $30 (remember the going rate is now $130!!!) and I still got the half-price line available, and Christy still has one of those great services that offer some shows at $4.50 (those are like the remainder bins in department stores, but hey, theater is theater!).

But Christy had gone ahead and paid full price for one show, the British import Warhorse. What did we know about it? We knew it had won the Tony Award for Best Play for 2010-11, and we knew that it had puppets. Oh, gosh. Puppets? Puppets. I mean, I did love Lion King and I found Avenue Q clever, but as a general rule, I am not excited about puppets. But I had read a review that called the play, “swoon-inducing.” Well, now. And it was produced by Lincoln Center—a sign of class and pedigree. So she plunked down the money for us for full price for Warhorse!

This was the most magical few hours of my summer, apart from time with family and friends. Warhorse was stunningly theatrical and charismatic and captivating.

The story is a pretty simple narrative—it comes from a novel for teens set around the Great War in England as Albert Narracott, the son of a ne’er-do-well, liquor-loving Devon farmer and a hard-working mum, yearns for a horse. When Dad, drunk as usual, buys Joey at an auction — an act of sibling rivalry toward his hoity-toity brother — young Albert takes on the animal’s care and feeding with deep enthusiasm. You probably guess one of the pleasures of this story—Warhorse speaks, cannily and brazenly, to that inner part of adults that cherishes childhood memories of a pet as one’s first — and possibly greatest — love. This is a show for people who revisit films like “Where the Red Fern Grows,” “The Yearling,” and “Old Yeller.”

But this is not just a play that registers as agreeable children’s entertainment. Joey, our half-thoroughbred horse, is a puppet. That sounds so one-dimensional, to just write, “Joey… is a puppet.” Joey is summoned into being by a team of strong and sensitive puppeteers. It is a puppet—yet this “puppet” is full of substance and soul. You watch this horse Joey, and admire the love Albert shares with Joey, and then your heart breaks as the father sells Joey to a World War I cavalry regiment.

So what is this Warhorse about? It is about imagination and majesty and love and adolescence and growing up and cold realities and hope and determination.

As the play unfolded, I did what I love to do during live performances—I watched the audience as often as I could. This was a matinee crowd and looked like a typical New York crowd—not the tourist crowd. I saw tears. I saw men take out handkerchiefs and choke back tears. Now come on—let’s get real. For a moment I admonished my inner self to stay observant and see the play for what it really was—a group of well-made, very large horse puppets. Two men can stand inside the puppet, one at the shoulders, and one under the hips and hind legs. A third man is at the side as if leading him along on a stafflike object resembling a lead line. I reminded myself that there were humans operating these beautifully engineered, lifelike horses. But as I watched, the cold reality melted away, and instead it was brilliant how the staff of Warhorse could move these staid New Yorkers to an emotional state.

The show’s storybook sensibility is enhanced by projections of drawings on what looks like an outsize strip of torn paper, which fluidly convey shifts of time and setting. After Joey is sold by Albert’s father to a cavalry regiment bound for France, the production’s look segues from idyll to nightmare, with harrowing images of walking corpses, enveloping shadows and death-machine tanks and guns. And of barbed wire, on which many a good horse met its end during World War I. Though human characters repeatedly bite the dust, it’s the horses on which our deeper hopes and fears are focused. And it’s the visions of their being fatally tangled in wire that are the show’s most unsettling. Albert goes in search of Joey through the hellish trenches of France. I won’t tell you how the story ends—Steven Spielberg has done a movie version of Warhorse which premieres in December.

But it’s not the actual narrative that is so breath-taking. It is the theatrical imagination to take an ordinary thing and make it far more extraordinary that it could have been or should have even been. Every so often, a pair of balladeers show up to sing about how we all “shall pass from this earth and its toiling” and be “only remembered for what we have done.” The implicit plea not to be forgotten applies not just to the villagers, soldiers and horses portrayed here, but also to theater, as an evanescent art that lives on only in audiences’ memories.

And also to the summer where precious evanescent reconnections are made with family and friends.

And also to the fragile beauty and ordinary-ness of school. Warhorse and school seem to intersect in quite a few ways for me, but perhaps in one important lens by which to view the unfolding of life’s adventures: both are about how the dirt that gets kicked in our faces sometimes gets transformed into magic dust.

Here I am—back for year 5 in Jordan…fresh from a summer and ready for the untold miracles of a school year, evanescent memories, cold realities, hope, determination, ordinary things transformed…I’d say that is “swoon-inducing” indeed.

Let’s begin anew!

Saturday, August 6, 2011

2-4-6

It has been seven weeks since I last checked in with you on the blog. I have been on my summer sabbatical in the United States doing perhaps what I do best—talking and eating. I take a sabbatical from the blog on one hand since I am not in work mode, and do not sit at a computer much in the summer, but also because I don’t know if my list of friends I see makes for interesting reading. Not that my friends are not interesting, but we often do not plow new ground, but re-connect, re-live, re-invigorate important relationships. I don’t know if the list of meals and friends makes for profound reading. I mean, in all of these wonderful and soul-stirring reconnections, nothing here is exactly new, but that is why I enjoy them so much. My summer is a collection of “my greatest hits” of relationships, and I enjoy the familiarity of them so much.

The title of this blog entry has to do with the way much of my summer is handled. I spend a good deal of time in the summer with my calendar out, scheduling friends and family for meals and visits. I choose “vacation” spots based on who I get to see, not a new locale, or incredible new beach, or really a new sight at all. I look at where I can go and with whom I can re-connect. Then in a rather OCD kind of fashion, I “schedule” people into time slots of generally 2-hour, 4-hour or 6-hour durations. That sounds so clinical, and I guess even impersonal, but my summer is actually one long personal re-connection with loved ones. This summer my travel companion Anne and I went to the Seattle area not just to revel in the beauty of the Olympic mountains and lakes of the Northwest region, but also to revel in the beauty of relationships with former students. However, even I have to chuckle at how the summer seems to break down into those 2-4-6 hour blocks. I will visit with dear friend Tony for four hours, go to a concert with dear friend Sylvia and enjoy a two hour visit, or since Dawn is always on warp speed, a 2-hour meal is sped by in lightning speed.

Two weeks ago I had a “cancellation,” i.e. one of my former students slotted for a “two hour” had a death in the family and had to jet off to Florida. Into this unexpected free time I went to the movies with Christy to see Woody Allen’s 41st film, Midnight in Paris. What a charming movie! It opens with a couple on holiday in Paris with her parents. The couple, Gil and Inez, are officially in love; he’s at work on a novel about “a guy who owns a nostalgia shop” and at the same time indulging in the virtual time travel that Paris affords a certain kind of visitor. Gil yearns to sit at a table where Hemingway drank wine or meet Scott and Zelda—and imagine that they just stepped out to take the air. Ahhhh…nostalgia…the good old days.

The definitive poem in English on the subject of cultural nostalgia may be a short verse by Robert Browning called “Memorabilia.” It begins with a gasp of astonishment — “Ah, did you once see Shelley plain?” — and ends with a shrug: “Well, I forget the rest.” Isn’t that always how it goes? The past seems so much more vivid, more substantial, than the present, and then it evaporates with the cold touch of reality. Some good old days are so alluring because we were not around, however much we wish we were. Midnight in Paris imagines what would happen if that wish came true. It is marvelously romantic, even though — or precisely because — it acknowledges the disappointment that shadows every genuine expression of romanticism. Midnight in Paris shows a Paris both golden and gray, breezy and melancholy, and immune to its own abundant clichés. Paris in the 1920s—now THAT was a time! Pablo Picasso, on the cusp of his painterly brilliance; Ernest Hemingway, hunting wild beasts and churning out prose of inner bravado; Gertrude Stein, at the hub of it all. And the surrealists—Dali, Bunuel, and Man Ray—striving valiantly to live life in the non sequitur.

And then it happens. One night as Gil is out for a midnight stroll, an extended vintage motor carriage comes by and picks him up. This is his magical ride to the Paris of yore, the Paris he's been pining for, the Paris he's been utterly romanticizing. All the luminaries are there. He takes this trip each night, developing relationships with them, and realizing their own human neuroses. Pablo Picasso, the uncertain lover; Ernest Hemingway, the unblinking blowhard; Gertrude Stein, enduring mother hen. And the surrealists—Dali, Bunuel, and Man Ray—striving ridiculously to live life in the non sequitur. This humanization of these icons of the art world is as amusing to Gil as it is to us. The electricity of the time is felt as he makes not just priceless connections and contacts, but friendships. The magic and charm of 1920s Paris is right out in front of everything, but at the same time, the imperfections begin to show, and not just the contrasts, but the comparisons to his present-time situation grow all the more evident. In fact, he realizes that the gift of nostalgia, the present of nostalgia, is actually a better understanding of the present day.

As I watched the film, and enjoyed the delightful return to a certain time period, the 1920s, and then La Belle Epoque, I realized that my summer was like this movie. Over and over this summer I have been like Gil, enjoying a trip into the past, reveling in the excitement of another age and the relationships of that time.

I began the summer with the ultimate trip down memory lane, a reunion of the Denison Singers, an event chronicled in the blog before, when we had met in the spring of 2008 and again in the fall of 2010. This four-day love-fest/song-fest is a doorway to the the 1980s, rekindling friendships and love of music that had been so important to my college years.

But the summer proved to have many doors to my past. This summer I found an old friend from the 1970s, a friend from Kirkwood that had meant so much for a decade, then as time does, we traveled down different paths. This friend David and I started visiting on Facebook, then on the phone, and we laughed about old jokes and fun times from our youth. On a trip to Gastonia and Charlotte, North Carolina, I opened the doors to the late 1980s as I visited with Cookie, and the early 1990s as I visited with Chuck. In my two weeks in the New York area, I opened the doors to the late 20th century and early 21st century as I visited with friends from the Hackley chapter of my life.

On the trip to Seattle, I visited with Stefan and Sean, such important figures in my 2000-2006 life, but then for a day, for a great four-hour slot I got to see Louise again (first time since 1993) and enjoyed the doorway to 1991-92.

Have I done anything new? Oh, I saw theater productions in New York, and especially enjoyed the phenomenal play, Warhorse, but my summer really has been like Gil’s happy adventures in Midnight in Paris—through the portals of a happy past. At the Frick Museum I bumped into Rika Burnham, the greatest museum educator I have ever known, and that little 10-minute slot was a wonderful doorway remembering how she electrified and inspired me in 1994-95. Then two nights ago when my dad and I went out to dinner in Cincinnati, we bumped into my two greatest high school teachers, sisters Mrs. Michaels and Mrs. Schneider. It was Mrs. Michaels’ birthday, and I got to enjoy these two icons and remember my debt to them for 30 years. I had a two-hour slot with Miss Wilson in July, the third in the troika of my greatest teachers of my youth…

As I look back over this summer, nothing here is exactly new, and that is what I wanted in my summer. But—and here is the important part of my summer and the parallel to this gem of a movie—very little is stale either. Woody Allen has gracefully evaded the trap of nostalgia with a credible blend of whimsy and wisdom. The movie makes clear that those good old days are seen through the clichéd rose-colored glasses, but the greatest point is how we live in the present, and the “present” of the present. That a shared love of Cole Porter’s music allows the movie character Gil to forge a connection in the present (and conceivably the future) with a young Parisian woman is a sign that his fetishizing of bygone days has been based on a mistake. Paris is perpetually alive, not because it houses the ghosts of the famous dead but because it is the repository and setting of so much of their work. And the purpose of all that old stuff is not to consign us to the past but rather to animate and enliven the present.

That is how I have felt about my 2-4-6 appointments of the summer! When I visited with Laura Hirschberg at Carmine’s Italian eatery (the scene of so many delightful meals for me in 1994-95) or enjoyed the annual visit with Sharon, it was not a musty trip down the ghosts on memory lane, but a reminder of where we come from, and how that animates and enlivens our present.

Ah, did I once see these childhood friends plain? How strange they seem, and new. And relevant. And enlivening.

The title of this blog entry has to do with the way much of my summer is handled. I spend a good deal of time in the summer with my calendar out, scheduling friends and family for meals and visits. I choose “vacation” spots based on who I get to see, not a new locale, or incredible new beach, or really a new sight at all. I look at where I can go and with whom I can re-connect. Then in a rather OCD kind of fashion, I “schedule” people into time slots of generally 2-hour, 4-hour or 6-hour durations. That sounds so clinical, and I guess even impersonal, but my summer is actually one long personal re-connection with loved ones. This summer my travel companion Anne and I went to the Seattle area not just to revel in the beauty of the Olympic mountains and lakes of the Northwest region, but also to revel in the beauty of relationships with former students. However, even I have to chuckle at how the summer seems to break down into those 2-4-6 hour blocks. I will visit with dear friend Tony for four hours, go to a concert with dear friend Sylvia and enjoy a two hour visit, or since Dawn is always on warp speed, a 2-hour meal is sped by in lightning speed.

Two weeks ago I had a “cancellation,” i.e. one of my former students slotted for a “two hour” had a death in the family and had to jet off to Florida. Into this unexpected free time I went to the movies with Christy to see Woody Allen’s 41st film, Midnight in Paris. What a charming movie! It opens with a couple on holiday in Paris with her parents. The couple, Gil and Inez, are officially in love; he’s at work on a novel about “a guy who owns a nostalgia shop” and at the same time indulging in the virtual time travel that Paris affords a certain kind of visitor. Gil yearns to sit at a table where Hemingway drank wine or meet Scott and Zelda—and imagine that they just stepped out to take the air. Ahhhh…nostalgia…the good old days.

The definitive poem in English on the subject of cultural nostalgia may be a short verse by Robert Browning called “Memorabilia.” It begins with a gasp of astonishment — “Ah, did you once see Shelley plain?” — and ends with a shrug: “Well, I forget the rest.” Isn’t that always how it goes? The past seems so much more vivid, more substantial, than the present, and then it evaporates with the cold touch of reality. Some good old days are so alluring because we were not around, however much we wish we were. Midnight in Paris imagines what would happen if that wish came true. It is marvelously romantic, even though — or precisely because — it acknowledges the disappointment that shadows every genuine expression of romanticism. Midnight in Paris shows a Paris both golden and gray, breezy and melancholy, and immune to its own abundant clichés. Paris in the 1920s—now THAT was a time! Pablo Picasso, on the cusp of his painterly brilliance; Ernest Hemingway, hunting wild beasts and churning out prose of inner bravado; Gertrude Stein, at the hub of it all. And the surrealists—Dali, Bunuel, and Man Ray—striving valiantly to live life in the non sequitur.

And then it happens. One night as Gil is out for a midnight stroll, an extended vintage motor carriage comes by and picks him up. This is his magical ride to the Paris of yore, the Paris he's been pining for, the Paris he's been utterly romanticizing. All the luminaries are there. He takes this trip each night, developing relationships with them, and realizing their own human neuroses. Pablo Picasso, the uncertain lover; Ernest Hemingway, the unblinking blowhard; Gertrude Stein, enduring mother hen. And the surrealists—Dali, Bunuel, and Man Ray—striving ridiculously to live life in the non sequitur. This humanization of these icons of the art world is as amusing to Gil as it is to us. The electricity of the time is felt as he makes not just priceless connections and contacts, but friendships. The magic and charm of 1920s Paris is right out in front of everything, but at the same time, the imperfections begin to show, and not just the contrasts, but the comparisons to his present-time situation grow all the more evident. In fact, he realizes that the gift of nostalgia, the present of nostalgia, is actually a better understanding of the present day.

As I watched the film, and enjoyed the delightful return to a certain time period, the 1920s, and then La Belle Epoque, I realized that my summer was like this movie. Over and over this summer I have been like Gil, enjoying a trip into the past, reveling in the excitement of another age and the relationships of that time.

I began the summer with the ultimate trip down memory lane, a reunion of the Denison Singers, an event chronicled in the blog before, when we had met in the spring of 2008 and again in the fall of 2010. This four-day love-fest/song-fest is a doorway to the the 1980s, rekindling friendships and love of music that had been so important to my college years.

But the summer proved to have many doors to my past. This summer I found an old friend from the 1970s, a friend from Kirkwood that had meant so much for a decade, then as time does, we traveled down different paths. This friend David and I started visiting on Facebook, then on the phone, and we laughed about old jokes and fun times from our youth. On a trip to Gastonia and Charlotte, North Carolina, I opened the doors to the late 1980s as I visited with Cookie, and the early 1990s as I visited with Chuck. In my two weeks in the New York area, I opened the doors to the late 20th century and early 21st century as I visited with friends from the Hackley chapter of my life.

On the trip to Seattle, I visited with Stefan and Sean, such important figures in my 2000-2006 life, but then for a day, for a great four-hour slot I got to see Louise again (first time since 1993) and enjoyed the doorway to 1991-92.

Have I done anything new? Oh, I saw theater productions in New York, and especially enjoyed the phenomenal play, Warhorse, but my summer really has been like Gil’s happy adventures in Midnight in Paris—through the portals of a happy past. At the Frick Museum I bumped into Rika Burnham, the greatest museum educator I have ever known, and that little 10-minute slot was a wonderful doorway remembering how she electrified and inspired me in 1994-95. Then two nights ago when my dad and I went out to dinner in Cincinnati, we bumped into my two greatest high school teachers, sisters Mrs. Michaels and Mrs. Schneider. It was Mrs. Michaels’ birthday, and I got to enjoy these two icons and remember my debt to them for 30 years. I had a two-hour slot with Miss Wilson in July, the third in the troika of my greatest teachers of my youth…

As I look back over this summer, nothing here is exactly new, and that is what I wanted in my summer. But—and here is the important part of my summer and the parallel to this gem of a movie—very little is stale either. Woody Allen has gracefully evaded the trap of nostalgia with a credible blend of whimsy and wisdom. The movie makes clear that those good old days are seen through the clichéd rose-colored glasses, but the greatest point is how we live in the present, and the “present” of the present. That a shared love of Cole Porter’s music allows the movie character Gil to forge a connection in the present (and conceivably the future) with a young Parisian woman is a sign that his fetishizing of bygone days has been based on a mistake. Paris is perpetually alive, not because it houses the ghosts of the famous dead but because it is the repository and setting of so much of their work. And the purpose of all that old stuff is not to consign us to the past but rather to animate and enliven the present.

That is how I have felt about my 2-4-6 appointments of the summer! When I visited with Laura Hirschberg at Carmine’s Italian eatery (the scene of so many delightful meals for me in 1994-95) or enjoyed the annual visit with Sharon, it was not a musty trip down the ghosts on memory lane, but a reminder of where we come from, and how that animates and enlivens our present.

Ah, did I once see these childhood friends plain? How strange they seem, and new. And relevant. And enlivening.

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Still in Wonder

In the first and second year of KA it was not uncommon that I would hear things from students like, “This Shakespeare is amazing!” or “I never read an entire book before,” or “Doing a play is more exciting than I imagined,” and of course the ubiquitous, “I never liked history before,” all absorbed and transfixed in the wonder of what they were doing and experiencing.

So here we are, at the very end of the fourth year of the school, two hours away from my getting on a plane that will take me to Paris and then to Cincinnati for summer vacation. What is it like now at the end of the fourth year?? For experienced educators, there can be great danger in losing the wonder. The improvements in the school or students that once thrilled us may become more familiar and academic. We may fall into the lethargy of using our minds but not always our hearts.

I have not found it hard to keep growing in wonder, however. I am still moved by what we have done in these four years, and the possibilities of where our students might go. It is still enormous work here, but very satisfying work. I am reminded of the great Stephen Sondheim song, “Finishing the Hat,” in Sunday in the Park With George when George sings, “Look, I made a hat…where there never was a hat.” Look—we made a school, where there never was a school!

It is not hard to keep growing in wonder when I look at two of my colleagues, both of whom have turned 70 in the last 3 weeks. Joan and Nancy have been teaching since the year I was born, and they are vibrant, warm, enthusiastic, optimistic, necessary, and full of wonder themselves. It is not hard when you work for such a good man as our headmaster, John. He is visionary, intelligent, humorous, considerate, hard-working, and believes in the “hat,” the mission of the school. Julianne has had an outstanding year, tightening up the structure of the school and ensuring that we run a tight ship. The tight ship means we can focus on all the good things of a school. It is not just structure, but a matrix upon which we can rely so we get to do the good stuff, to keep exploring new layers of wonder.

I am still in wonder at what is going on in the Arab world. As I look back on the last six months in this region of the world, at what many call, “The Arab Spring,” I am in wonder. How interesting, indeed, what poetic justice, you might say, that Osama bin Laden died at the exact moment he was made irrelevant by the Arab Spring. None of the wave of democratic uprisings transforming the Islamic world were inspired by bin Laden’s despotic, twisted version of Islam. Instead, they were fueled by waves of well-educated young people, including women, who want the chance to vote in free and open elections. No one in Liberation Square in Cairo chanted his name. I am still in wonder at the possibilities at what may take place.

Of course none of us knows what the four years at KA will actually do/for/to our students. But at the end of this year it is marvelous to look back at a calm year, an invigorating year, a year of great scholarship, of great thinking, of empathy, of respect and responsibility, of bittersweet loss as we graduated our first four-year class.

So I want you to know, I am still in wonder at this project. Now, I didn’t write as much on the blog this school year. In 2007-08 I wrote 90 blog entries, and then the next year I wrote 72 blog entries. In 2009-10 I wrote 63 blog entries, and this school year I only wrote 48 blog entries. Of course the excitement of seeing a camel is no longer new, but the wonder at what our work can accomplish still sets my heart racing and my brain zigzagging.

But it is time for summer. I will now take my annual sabbatical from the blog, with an update in July, but a break from the writing and pondering and planning of the blog. Someday I would love to convey some of the stories that don’t make it into the blog. It would be interesting to describe for you the horror and the humor of this insane teacher’s breakdown. It would be interesting to relay what the loss of a friendship means. It would be interesting to try and sum up what it is like to work with some difficult and inscrutable colleagues. But the point of this blog is not to air dirty laundry anyway or vent my spleen. I write this blog to communicate the wonder I feel as this project unfolds.

So here is to summer…here is a poem suggested to me by Steve Shapiro, a friend I made on the conference to Kathmandu last fall. The picture at the top of the page is the subject of the poem, and a kind of flower seen around in Jordan in April.

Camas Lilies

Consider the lilies of the field,

the blue banks of camas opening

into acres of sky along the road.

Would the longing to lie down

and be washed by that beauty

abate if you knew their usefulness,

how the natives ground bulbs

for flour, how the settler’s hogs

uprooted them, grunting in gleeful

oblivion as the flowers fell?

And you—what of your rushed and

useful life? Imagine setting it all down—

papers, plans, appointments, everything,

leaving only a note: “Gone to the fields

to be lovely. Be back when I’m through

with blooming.”

Even now, unneeded and uneaten,

the camas lilies gaze out above the grass

from their tender blue eyes.

Even in sleep your life will shine.

Make no mistake.

Of course, your work will always matter.

Yet Solomon in all his glory

was not arrayed like one of these.-Lynn Ungar

So in about two hours I head out for the summer. The first day of work is exactly 8 weeks from today. But for right now, I am going to do exactly what the poem suggests, I am going to set “it all down—the papers, plans, appointments, everything.” I might also do exactly as the poem suggests and when I turn the key in the apartment door lock, I may tape a note on my door: “Gone to the fields to be lovely. Be back when I’m through with blooming.”

Ahhhh…enjoy the summer. Steep yourself in wonder. Go to your own fields and be lovely!

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Camping With Henry and Tom

Back in the day (have I ever mentioned how much I don’t like that imprecise phrase??!) when I first moved to New York with the Klingenstein Fellowship (I don’t like the phrase because as a historian, I like the precision of saying 1994-95 instead of the vague, generic, ‘back in the day…’) among the dozens of plays I saw in that ‘Cinderella’ year was a play called Camping With Henry and Tom. Part of the gimmick of this play was wondering what would real important people talk about on a camping trip. The ‘Henry and Tom’ of the title refer to the real important people of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison who actually did go on a real camping trip with the head of state, the President of the United States, Warring Harding, back in the early 1920s. It was a satisfying play, and does allow us to think of leaders of countries and leaders of industries kicking back and going camping.

Last month I had my own version of Camping With Henry and Tom. Now from the picture above, it would look like a strange version of Henry and Tom. No, those two colleagues are Lyndy and Jill, colleagues who work in the University Counseling Office here at KA. Last month we had the opportunity to go with the senior class on a camping trip with His Majesty. I got to go on a camping trip with a head of state! Not too much unlike when buddies Ford and Edison went with sitting President Harding. Ha!

I am not the biggest fan of camping, but let’s face it, the company here makes the difference! His Majesty started a tradition last year of taking the senior class on a camping trip and of course it is an exciting prospect to join His Majesty down in Wadi Rum in southern Jordan for an overnight camping trip.

A couple days before the camping trip I had a call from one of our administrators and she said, “I am going to ask you something weird, but I really want to know. Do you like to ride motorcycles?” Yes, it was strange and random, but I answered that I had not ever ridden a motorcycle and I had once promised my parents I would not ride one. As she inquired, I kind of guessed the purpose of the call. His Majesty is a big fan of motorcycle riding, and she did not want to say, but I figured I was turning down a chance to ride motorcycles with the King. Yes, indeed, that was the case, but I am not sure I should have answered any differently.

Anyway, camping day arrives, and the senior class and a dozen chaperones board the busses for the four hour trip down to this mysterious beautiful desert spot that is captured forever in Lawrence of Arabia. When we arrive we are met by a fleet of about 25 silver SUVs that will whisk us to the camp site. It was impressive since the other two times I had been down there I had taken rides in two of the most battered, uncomfortable pick-up trucks I could have imagined.

When we arrive at the camp site, we meet the team from Protocol from the Royal Court who tell us the program of the camping adventure. We have lunch and then can wander around the craggy rocks of the area, and then we can enjoy all the guns at the shooting range. His Majesty is a big military guy, and I had been told how he makes these guns, real guns, available for shooting practice. As everyone finds tents (and by the way, thankfully, these are tents with floors, electric lights, sunscreen, and hand sanitizer—this may turn out to be my kind of camping!!) we relax in the various venues set up for the kids to enjoy themselves with unlimited soda and candy and the lunch station, the tents, the volley ball area, what will be an enormous camp fire, and the shooting range.

I don’t know whether I should go and shoot or not—it had been since YMCA camp in the 1970s when I had done any shooting, and those of course were BB guns. But when Lyndy and Jill went over to shoot, I thought, I might as well try everything our camp experience has to offer. There were pistols and rifles and machine guns. Real ones! Some gentlemen were there to help us learn how to shoot and how not to get hurt from the kickback of the gun. My parents would be pleased to know that after the shooting experience I would not want to re-live my childhood and shoot more or change my life goals and join the military. But it was an experience to hold a real gun and shoot at a target.

After a little while His Majesty arrived, eager to meet the students and visit with them…and take them on tank rides! He arrived in jeans and a t-shirt, and of course he cuts quite a charismatic figure. He said he loves to take people on tank rides and the tank could handle about 4 people inside the tank, and then about 12 people could ride on the tank as he drove around the desert. As he got in for the first ride, he said to the students around him, “Now I can’t always hear when I drive this thing, so if it gets too uncomfortable, just tap me on the head so I know.”

Let’s just process all of this…a head of state, in jeans and a t-shirt, taking giddy students and teachers around, in a real tank, and if we have a problem we could tap him on the head.

Okay.

Obviously I had to go on a tank ride! The picture above is from inside the tank when Lyndy and Jill and I rode inside the tank. Then we joined the line to jump on top for the ride on top of the tank. The inside ride was hot and not a very good view. The outside ride was exciting, yet incredibly dusty and I held on for dear life as His Majesty zoomed over the sand dunes in the desert. Neither ride is something I thought I might ever do when I ventured into the classroom for the first time in the fall of 1986!!

Before the camping trip the Royal Court had impressed on all of us that we could indeed take pictures on the camping trip, pictures with His Majesty, but we were asked that we use them strictly for private purposes and that we not put pictures of him on the internet. As I have come to see, the Royal Court wants to control the images of the king, and so we were asked not to put them on facebook or blogs. That is why you see a picture of me with Lyndy and Jill, a la Henry and Tom, and not one of me with the king. But if you come over and see me sometime, I will show you this great shot of me leaning up against the tank chatting with the king. Now I have a little sense of what camping with Henry and Tom was like!

That night we had a dinner—and this was a buffet dinner that forever will make my mouth water. Some of the best steak, some of the best food was ‘rustled’ up for us. Actually, I should thank the staff, the staff of about 30 whose job it was to make sure our camping trip was a great experience.

During dinner a student came and told me that John, our headmaster, wanted to see me.

I went over and John said, “His Majesty would like to talk with you one-on-one.” No way! So I walk over and sit down and this man who seemed to like the same foods on the buffet that I did, put his plate down, and said, “I want to thank you for the work you did with Hussein this year. He enjoyed your class more than I can say.” In this chat, what was so wonderful was the look in his eye. I am blessed to say I have seen that look before—the look of a parent so grateful that his or her child had been transformed by something in school. He and I talked about art history, and about writing, and about school, and about adolescence and teaching, and about how he and his wife do not know much about art history but they are amazed at what their son knows.

I have seen this man on campus many times over these four years, as a man proud to have started a school like this, as a man who realizes everyone wants to meet him, shake his hand, have a photo taken, as a man with security guards, usually in a suit and school tie. But here I was, sitting casually with this man, this head of state, and I was talking solely to a grateful and interested father. I guess he doesn’t get to do that all that much—he doesn’t get to do all the parent’s day things and parent-teacher conferences. He and I talked about the incredible leaps Hussein had made as a scholar this year, and he very kindly said, “You will be the teacher he remembers as the teacher that helped him grow the most.” Of course I was trying to tell him about how wonderful his son was, but he wanted to make sure I knew how proud and grateful he was. I said, “I get to teach him again next year too. I know it will be a great year.”

The conversation came to an end. But what a wonderful moment. Stripped of any folderol, it was just a warm parent-teacher conference sitting by a fire in the deserts of southern Jordan. Soon after that His Majesty spent the next couple hours talking with a gaggle of kids about politics and college and leaving KA and Jordan and their families. He was clearly pleased. He got to sit and talk and be as real as any generous man could be. He was obviously happy and in his element.

Of course the senior class stayed up all night. We knew it was in the cards! The adults, well, some of them, took shifts of chaperoning, and shifts of 90-minute naps so we could monitor loosely and make sure everything went well. The following morning had a breakfast buffet and then a trek across the terrain and a climb up the biggest sand dune I have ever seen in my whole life.

My shoes are still covered in the ochre and rust-colored sand of Wadi Rum, and I still don’t know if I am a camper, per se, but what an extraordinary time with a class I have enjoyed so well, and getting to talk to a father about how well his son has done. A satisfying time.

Friday, June 17, 2011

The People In The Picture

I might have missed this wonderful little art exhibit if I hadn’t been mad at the moment.

Okay, back in spring break I was going to meet Christy at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Now if you know Christy, you know that among her many gifts, punctuality is not in that line-up. I called. I texted. She was on her way. I waited. Finally, we met up. What was most egregious to me is that when she had arrived she didn’t even look for me! She just figured no one would wait for her since she was so late. So she went about looking around in the Met while I had continued to wait. Then when we finally met up, and I heard the tale of how she didn’t wait anticipating I wouldn’t wait…well, I was steamed.

To blow off some steam I decided to duck into this small exhibit in the Met and let myself cool down.

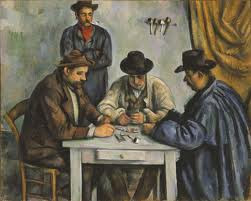

The exhibit was something about this Cezanne painting called The Card Players. I figured I would admire the Cezanne and then resume the afternoon plans.

But in this little exhibit on this seemingly mundane painting, as usual at the Met, I was greeted with a world of knowledge, and realized yet again how easy it is to overlook something. Or certainly to forget that there is probably more depth from what first meets the eye.

Look at the painting at the top. It is very typical Cezanne. He paints with a rough texture, reminding the viewer of the painterly qualities of composition and how he loves to explore the “volumetrics” of people and subjects in his paintings.

But there was more. Cezanne had picked a topic in art history (card playing) that had a long history—I kind of knew this, but not to the extent I would learn in the next half hour! For about 500 years painters had taken up the subject of card playing so as to moralize and weigh in on the dangers of bad choices in one’s life. Durer and Caravaggio are two of the famous artists who had added to the debate about how card playing could ruin your life.

But the curator of the show wrote that Cezanne had no desire to sermonize about the evils or sins of card playing. He simply wanted to pick up a thread of art history, the oft-told tale of card playing, and ask the viewer to look at the people playing. Cezanne had no interest in trying to shape the moral life of a young viewer. He wanted us to look at the people playing cards, not the demon instruments in their hands. Cezanne asked the gardeners at his estate to pose for the painting. Of course they must have been surprised—it was common knowledge that there are certain people who make for subjects of art works, and certain people who definitely do not have the status to be the subject of an art work.

As I walked around the room—the Met had put other examples of the moralizing card player paintings and etchings around—I saw what Cezanne was going for. Cezanne was doing what really great teachers try and do. He wanted us to look more deeply, beyond the surface or concrete subject of what was going on. He wrote, and the Met quoted him, that he wanted his hardscrabble gardeners to look important, to have the same kind of volume and value as a pharaoh from Egypt, or a king from Europe, or a banker.

I quickly got over my frustration with the Late One (I have had to do that many times in the nearly 17 years I have known Christy!) and went and got her to show her around the room. As we walked around the room, we realized how easy it is to overlook something, or someone, seemingly mundane. There is always a story there, for us to explore. Cezanne was urging us to get past silly moralizing (I won’t even begin to make jokes about politicians who spout Family Values and then end up resigning amidst tears and shame) and focus on people. Who are these men? What are their stories? What do we learn about them? What more do we need to know to better understand them?

What a lovely lesson and reminder in that quick little art exhibit on Cezanne.

Later that week Christy and I went to see a Broadway show about which we knew next to nothing. We knew it starred the spectacular performer Donna Murphy and we knew the title, The People In The Picture, and we knew we got to go for $4 each. What else does one need to know???

As we entered the theater (the rehabbed old disco palace Studio 54) we saw all these black and white photos up on the walls of families we didn’t know. The stage had been created as one giant picture frame angled out towards the audience with an enormous crack in it. As the musical began a photograph of unknown people projected above the stage. Who were these people? What was the point? It turns out this was a musical about an episode in the Holocaust.

Other than the creation of the state of Israel, the greatest and most profound reaction to the Holocaust has been the extraordinary outpouring of art that has attempted to come to terms with this egregious event, from The Diary of Ann Frank to Cabaret to Schindler’s List and on and on. The People In The Picture, this heart stopping musical, would be the most recent attempt. The People In The Picture asks us to take a hard look at the suffering and loss that resulted from this diaspora and tragedy.

The people in this picture of the show is “The Warsaw Gang,” a ragtag troupe of actors barely surviving, but finding solace and entertaining their fellow Jews amidst the pogroms and poverty of 1930s Poland. Their story is told in flashback as troupe leader Raisel, nearing the end of her life, shares her life’s journey with her granddaughter, Jennie.

In her memories, The Warsaw Gang literally comes to life on stage in all its glory and ultimate tragedy. And even though we know from the start that Raisel survived the Holocaust, it is only at the play’s climax that we learn the terrible toll it took on her and her unhappy daughter.

The triumph of The People In The Picture is that the show insists upon—and earns—heroic stature for even small gestures of humanity. A man loses his life over bringing a doll to a little girl. Another man is knifed to death because he cannot ultimately joke his way out the anti-Semitism of bullies. One by one the good and noble people we have come to admire and understand from the picture are murdered. By the end of the show we know so much more, we feel so much more for the people in the picture.

Donna Murphy miraculously morphs back and forth between robust womanhood and old age. I watched how as one number ended, simply by taking her glasses out of her pocket and rolling up her sleeves, it was as if she aged 40 years. She was marvelous.

Christy and I loved the show. But there were many in the audience who thought it was ridiculous and stupid. At intermission we heard two young, 20-somethings harrumphing their way out of the theater uttering, “That’s 75 minutes of my life I won’t ever get back.” They just didn’t get it. Oh well. At the end of the show there was a “talk-back” with some of the actors and creative team of the show. Christy and I love these things—we always learn more and get more juicy context about a show.

The people who stayed for the talk-back, maybe only about 30, glowed with appreciation for the show. Many of them were grand-children of survivors of the Holocaust, and they always struggled how to better understand the enormous sufferings of their grandparents. The writer of the show said that that was why she wrote this piece. She found a few photographs from her parents and just wondered about their lives, she needed to figure out what made these people in these pictures tick. The grateful audience applauded them and thanked them for humanizing this period in a new way. Christy and I walked home, grateful that in that city we experienced so many moments in which we learned and remembered to consider people and incidences we might overlook. As I anticipated coming back to Jordan after spring break to finish, I Never Saw Another Butterfly, I relished that opportunity to think about those sepia pictures and their lives.

So—one art exhibit reminds us that attention must be paid to even the card players in a painting. And another musical urges us to consider what goes on beyond the borders of a photograph. How stunning to have these reminders—almost like the biblical urgency to “consider the lilies of the field.”

As I pack up for the year, think about graduation and all the hundreds of pictures taken at the conclusion of this school year, it is important to think of those pictures and the people. Decades from now will viewers know the struggles, experience the joys that brought those teen-agers to that moment? Will the men and women look back and see beyond the tossing of a hat, or see that the smile is so well-earned because it was hard to get there? How good to remember to look beyond the borders of the photographs we find and try and re-create the epic battles and triumphs that allowed that photograph to come into being.

Oh, I love learning from art and theater! I am reminded of the great quotation from the snarky writer Paul Rudnick: “Most convicted felons are just people who were not taken to museums or Broadway musicals as children.”

She asked, gingerly

Perhaps the most intriguing question posed to me this school year came a few months ago when a student asked, gingerly, indeed politely but delicately, “Why are Americans so obsessed with the Holocaust?”As with everything, don’t you know, context helps us explain and understand things more.

This student, one of that wonderful coterie of students at KA I have taught every day for the last four years, is Jordanian-Palestinian-Lebanese but has lived most of her life in California. She really does understand and enjoy both worlds.

Her question did not come out of nowhere. We had been studying the Berlin Olympics of 1936, and one of the saddest realizations of the aftermath of studying that Olympics designed and executed with German precision and taste, is that many of the European Jewish athletes who attended and won medals in Berlin would later die in Nazi concentration camps. Naturally, our discussion morphed into the meaning and the teaching of the Holocaust.

When this diligent, happy, marvelous student asked her question, “Why are Americans so obsessed with the Holocaust?” many faces quickly looked to see if I was upset with her query. But they were riveted with what my answer might be. Of course I wasn’t upset—one of the greatest joys of my four years in Jordan is that I am often allowed to be out of my comfort zone and learn things, reflect on things, decide about things that would not come up in the United States.

This excellent historian then asked, “Do Americans study the Armenian genocide as much? Do they study the kulaks in the Soviet Union? the Filipinos under the care of the Americans? The Chinese of Nanking under the Japanese occupation in the 1930s? The Muslims of Bosnia in 1990s Yugoslavia?” Again, she did not ask any of these rapid-fire questions stridently. As we all know, Americans have little interest or knowledge about these other examples of genocides or mass killings. In our History of the 20th Century class, we had discussed all those other examples, and as you might imagine, the class sat dumb-founded at the too-many examples of reckless mass killings and carnage of the 20th century. She really wanted to know—why, then, are Americans so interested in the Holocaust?

Here was a great teachable moment—we wondered if the answer is that there are so many people of Jewish descent? No, that is not the case. Nor can it be that so many Americans have known Holocaust survivors. (I met my first survivor when I moved to New York in 1994.) Is it guilt over the Holocaust that creates such zeal to teach about it in American curricula? Off the top of my head I wondered, if in part, Americans have been drawn to the Holocaust because of the sheer amount of evidence left to us by the Germans. The Germans documented things so well—in large part since they were creating a “Museum of Inferiority” which would showcase the Final Solution in a seriously-folks-they-planned-it-for-real-museum which would have been in Prague. The photographs, film, interviews, statistics, etc. all are so available that that makes it so much in the forefront of our brains. There is not much evidence about the Armenian genocide of 1919. Indeed, there is so little evidence that the Turkish government insists it is exaggerated and did not really happen as survivors claim. And what of the movies? There have been dozens of films about the Holocaust in the last 45-50 years…where are the Hollywood films about the other peoples’ plights?

It made for a great discussion, simply trying to figure out why Americans have studied that example of injustice and hatred more than any other world history grievance. And, then I asked, ”Why are Arabs so opposed to any mention or study of the Holocaust?”

I knew most of what their responses were, but it was instructive to listen to each other and formulate an answer. None of their answers really had anything to do with anti-Semitism, although that would be what most of us would assume. Some of the answers lay in the question, simply why can’t there be a balance of all people’s suffering? One student finally cracked open what some wondered would come to light, or at least public light in our class. “The state of Israel has capitalized so much on the Holocaust, and has cheapened it, so that some people are just tired of that being the answer and reason for everything.”

This sentiment is one of the most important to understand about the Middle East, but not just the so-called exploitation of the Holocaust. It cuts to the core of the most searing problem in Jordan—the issue of Palestine.

Let’s go back to all this context…I mentioned this exchange in class today because I wanted to set the stage for why it was daring to produce I Never Saw Another Butterfly here in Jordan. Yes, it is a beautiful play about survival, about family and friends, and a memorable teacher. But the subject makes some people uncomfortable and some would prefer it never be broached. Never. Not in school. Certainly not in the faculty lounge.

I had the idea to produce my warhorse play about the children’s concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, not simply to raise the idea of the Holocaust here. In some ways, the Holocaust does not intrude much on the play. You never see a Nazi, and there is no gratuitous violence. But I got the idea for the play when last autumn a group of student-actors appeared at our school doing monologues about the Israeli occupation and war of 2009. As these teen-agers performed their “Gaza Monologues” I was struck by the parallels between this contemporary drama and I Never Saw Another Butterfly. But of course, it shouldn’t have been so surprising—both were dramas about the refugee experience, the phenomena of having daily life disrupted or shunted due to an occupation force. I couldn’t get over how similar the feelings were. I went to our headmaster and suggested I direct I Never Saw Another Butterfly and pair it with the Gaza Monologues. I made clear that we were tackling a subject that could create controversy. He read the play and agreed that the message needed to get out there.

Again, some context helps enormously to see the magnitude of this play choice. Yes, I had directed the play a bazillion times in the USA, but in this region of the world schools are not encouraged to teach about the Holocaust. Pages are ripped out of some textbooks, The Diary of Anne Frank is banned, and I swear that I heard that Fiddler on the Roof was performed in Amman with all the Jewish references taken out! Seriously????!!!

After I spoke with our headmaster, I spoke with Fatina, my friend and colleague of four years. I go to her with every question I have about the Middle East (“Why do your people do this?” I have often asked, and then she sighs, and says, “My people do this because…”). I told her about I Never Saw Another Butterfly and said, “Do you think we can, we should, do this play?” Fatina said it would create some tension, but that definitely the message of the play was vital. Fatina is so important here, and she does insist on teaching the Holocaust even though few teachers in this region would. She teaches about it so that the students understand the desperate need for a national homeland for Jews after World War II.

That lies at the heart of the problem, the tension, the confusion. When we discussed in class about why Jordanians don’t want to discuss the Holocaust, or want to deny it happened, it again is not anti-Semitism, per se. As one student said, “There is so much pain for us associated with the formation of Israel." Over half of Jordan is comprised of refugees expelled from Israel in 1948 or in 1967. I mentioned in class then about the possibility of doing a play about this. I just happened to have a scene from I Never Saw Another Butterfly, ready to read and discuss…I had anticipated the discussion. The scene was the family scene, and if you changed the names and place of Prague, it could easily have been a scene understood by Palestinian families in 1948 and 1967. They understood the worry and fear that everything they knew would change.

The class was extremely interested in the play. One of my most vocal and dynamic students suggested we didn’t need to pair the two plays—he thought it important for our community to really consider the feelings and attitudes of this Jewish family. Of course when the play schedule was shortened, as I mentioned in the other blog, it became necessary to toss out the comparison of the two plays.

However, it is never as simple as collecting some key person’s approvals. On the day of the play, some people at school became quite upset that I would offer a play that would remind people of the pain of the Nakba, the great 1948 expulsion of Palestinians (or worse, glorify the ones who did the expelling). The headmaster and Julianne steadfastly supported me, but a handful of people were quite hurt that I would want to hurt the community so much. I offered to speak to anyone and explain that the play is not a political play, it is not about Zionism, it is a play about survival, and friends and family, and the refugee heartache. Only one of those so upset would speak to me, and while I know they were upset at me, I also did not want our school to go along with the norm and not discuss the issue. It is not about sympathy for Israel, it is about the triumph of the human spirit. It was about the fact that sadly, these experiences have happened too often in the last century and the experiences seem more similar than not.

I did not want to belabor the point that when the Nazis created their Final Solution genocide was the goal. As much as the refugee experience has been similar, Israel has not had that genocidal goal. But I did feel that the experiences had parallels. It made it all the more interesting to watch young, vibrant, Muslim Farah tackle the part of Raya/Raja.

One last little tidbit about context: I told them of a story about how I formed an opinion and how socialization and stories can help construct our opinions. I told them about how in 1978, I watched the Oscars for the very first time. As an 8th grader I was in love with the movies, and watched and cheered on the movie stars. When Vanessa Redgrave won her Best Supporting Oscar for Julia, she was booed and heckled. I thought, “Who is this awful woman? She must be hideous since all of Hollywood is booing her!” A few years later she wins the part of a Holocaust survivor in a movie, and again is castigated for her beliefs.

At the time I just figured, given the Hollywood reaction, this Vanessa Redgrave must be a horrible person. I later came to understand she came under such fire because she believed that Palestinians deserved the right to return, that Israel had acted improperly in the 1948 expulsion of Palestinians.

We sat in class discussing how our impressions are made, how heroes and villains are born and treated, and reminded ourselves to look for as much context as possible to better understand the many facets of the complicated issues of our time.

One last comment about the play—it was received well, but for some it is hard to get past the pain. A student said to Fatina, “That was the first time I felt sorry for a Jew. That surprised me.” Fatina considered the situation and said, “It wasn’t that you thought of her as Jewish or not—she was simply human.”

Human. Humanity. Maybe we are getting closer all the time…

This student, one of that wonderful coterie of students at KA I have taught every day for the last four years, is Jordanian-Palestinian-Lebanese but has lived most of her life in California. She really does understand and enjoy both worlds.

Her question did not come out of nowhere. We had been studying the Berlin Olympics of 1936, and one of the saddest realizations of the aftermath of studying that Olympics designed and executed with German precision and taste, is that many of the European Jewish athletes who attended and won medals in Berlin would later die in Nazi concentration camps. Naturally, our discussion morphed into the meaning and the teaching of the Holocaust.

When this diligent, happy, marvelous student asked her question, “Why are Americans so obsessed with the Holocaust?” many faces quickly looked to see if I was upset with her query. But they were riveted with what my answer might be. Of course I wasn’t upset—one of the greatest joys of my four years in Jordan is that I am often allowed to be out of my comfort zone and learn things, reflect on things, decide about things that would not come up in the United States.

This excellent historian then asked, “Do Americans study the Armenian genocide as much? Do they study the kulaks in the Soviet Union? the Filipinos under the care of the Americans? The Chinese of Nanking under the Japanese occupation in the 1930s? The Muslims of Bosnia in 1990s Yugoslavia?” Again, she did not ask any of these rapid-fire questions stridently. As we all know, Americans have little interest or knowledge about these other examples of genocides or mass killings. In our History of the 20th Century class, we had discussed all those other examples, and as you might imagine, the class sat dumb-founded at the too-many examples of reckless mass killings and carnage of the 20th century. She really wanted to know—why, then, are Americans so interested in the Holocaust?

Here was a great teachable moment—we wondered if the answer is that there are so many people of Jewish descent? No, that is not the case. Nor can it be that so many Americans have known Holocaust survivors. (I met my first survivor when I moved to New York in 1994.) Is it guilt over the Holocaust that creates such zeal to teach about it in American curricula? Off the top of my head I wondered, if in part, Americans have been drawn to the Holocaust because of the sheer amount of evidence left to us by the Germans. The Germans documented things so well—in large part since they were creating a “Museum of Inferiority” which would showcase the Final Solution in a seriously-folks-they-planned-it-for-real-museum which would have been in Prague. The photographs, film, interviews, statistics, etc. all are so available that that makes it so much in the forefront of our brains. There is not much evidence about the Armenian genocide of 1919. Indeed, there is so little evidence that the Turkish government insists it is exaggerated and did not really happen as survivors claim. And what of the movies? There have been dozens of films about the Holocaust in the last 45-50 years…where are the Hollywood films about the other peoples’ plights?

It made for a great discussion, simply trying to figure out why Americans have studied that example of injustice and hatred more than any other world history grievance. And, then I asked, ”Why are Arabs so opposed to any mention or study of the Holocaust?”

I knew most of what their responses were, but it was instructive to listen to each other and formulate an answer. None of their answers really had anything to do with anti-Semitism, although that would be what most of us would assume. Some of the answers lay in the question, simply why can’t there be a balance of all people’s suffering? One student finally cracked open what some wondered would come to light, or at least public light in our class. “The state of Israel has capitalized so much on the Holocaust, and has cheapened it, so that some people are just tired of that being the answer and reason for everything.”

This sentiment is one of the most important to understand about the Middle East, but not just the so-called exploitation of the Holocaust. It cuts to the core of the most searing problem in Jordan—the issue of Palestine.

Let’s go back to all this context…I mentioned this exchange in class today because I wanted to set the stage for why it was daring to produce I Never Saw Another Butterfly here in Jordan. Yes, it is a beautiful play about survival, about family and friends, and a memorable teacher. But the subject makes some people uncomfortable and some would prefer it never be broached. Never. Not in school. Certainly not in the faculty lounge.

I had the idea to produce my warhorse play about the children’s concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, not simply to raise the idea of the Holocaust here. In some ways, the Holocaust does not intrude much on the play. You never see a Nazi, and there is no gratuitous violence. But I got the idea for the play when last autumn a group of student-actors appeared at our school doing monologues about the Israeli occupation and war of 2009. As these teen-agers performed their “Gaza Monologues” I was struck by the parallels between this contemporary drama and I Never Saw Another Butterfly. But of course, it shouldn’t have been so surprising—both were dramas about the refugee experience, the phenomena of having daily life disrupted or shunted due to an occupation force. I couldn’t get over how similar the feelings were. I went to our headmaster and suggested I direct I Never Saw Another Butterfly and pair it with the Gaza Monologues. I made clear that we were tackling a subject that could create controversy. He read the play and agreed that the message needed to get out there.

Again, some context helps enormously to see the magnitude of this play choice. Yes, I had directed the play a bazillion times in the USA, but in this region of the world schools are not encouraged to teach about the Holocaust. Pages are ripped out of some textbooks, The Diary of Anne Frank is banned, and I swear that I heard that Fiddler on the Roof was performed in Amman with all the Jewish references taken out! Seriously????!!!

After I spoke with our headmaster, I spoke with Fatina, my friend and colleague of four years. I go to her with every question I have about the Middle East (“Why do your people do this?” I have often asked, and then she sighs, and says, “My people do this because…”). I told her about I Never Saw Another Butterfly and said, “Do you think we can, we should, do this play?” Fatina said it would create some tension, but that definitely the message of the play was vital. Fatina is so important here, and she does insist on teaching the Holocaust even though few teachers in this region would. She teaches about it so that the students understand the desperate need for a national homeland for Jews after World War II.

That lies at the heart of the problem, the tension, the confusion. When we discussed in class about why Jordanians don’t want to discuss the Holocaust, or want to deny it happened, it again is not anti-Semitism, per se. As one student said, “There is so much pain for us associated with the formation of Israel." Over half of Jordan is comprised of refugees expelled from Israel in 1948 or in 1967. I mentioned in class then about the possibility of doing a play about this. I just happened to have a scene from I Never Saw Another Butterfly, ready to read and discuss…I had anticipated the discussion. The scene was the family scene, and if you changed the names and place of Prague, it could easily have been a scene understood by Palestinian families in 1948 and 1967. They understood the worry and fear that everything they knew would change.

The class was extremely interested in the play. One of my most vocal and dynamic students suggested we didn’t need to pair the two plays—he thought it important for our community to really consider the feelings and attitudes of this Jewish family. Of course when the play schedule was shortened, as I mentioned in the other blog, it became necessary to toss out the comparison of the two plays.

However, it is never as simple as collecting some key person’s approvals. On the day of the play, some people at school became quite upset that I would offer a play that would remind people of the pain of the Nakba, the great 1948 expulsion of Palestinians (or worse, glorify the ones who did the expelling). The headmaster and Julianne steadfastly supported me, but a handful of people were quite hurt that I would want to hurt the community so much. I offered to speak to anyone and explain that the play is not a political play, it is not about Zionism, it is a play about survival, and friends and family, and the refugee heartache. Only one of those so upset would speak to me, and while I know they were upset at me, I also did not want our school to go along with the norm and not discuss the issue. It is not about sympathy for Israel, it is about the triumph of the human spirit. It was about the fact that sadly, these experiences have happened too often in the last century and the experiences seem more similar than not.

I did not want to belabor the point that when the Nazis created their Final Solution genocide was the goal. As much as the refugee experience has been similar, Israel has not had that genocidal goal. But I did feel that the experiences had parallels. It made it all the more interesting to watch young, vibrant, Muslim Farah tackle the part of Raya/Raja.